The 1961 Philadelphia Phillies season was the 79th in franchise history. The Phillies finished the season in last place in the National League at 47–107, 46 games behind the NL Champion Cincinnati Reds. The team lost 23 games in a row, the most in MLB history.

1962 New York Mets

The 1962 New York Mets season was the first regular season for the Mets. They went 40–120 (.250) and finished tenth and last in the National League, 60+1⁄2 games behind the NL Champion San Francisco Giants, who had once called New York home. The Mets’ 120 losses are the most by any MLB team in one season. Since then, the 2003 Detroit Tigers, 2018 Orioles, and 2023 Oakland Athletics have come the closest to matching this mark, at 43–119 (.265), 47–115 (.290), and 50–112 respectively.

Spruce Goose

The Spruce Goose is a prototype strategic airlift flying boat designed and built by the Hughes Aircraft company. Intended as a transatlantic flight transport for use during World War II, it was not completed in time to be used in the war. The aircraft made only one brief flight, on November 2, 1947, and the project never advanced beyond the prototype.

Built from wood because of wartime restrictions on the use of aluminum and concerns about weight, the aircraft was nicknamed the Spruce Goose by critics, although it was made almost entirely of birch.

Twinkies Lip Balm

Launched in 2004, Twinkies Lip balm transforms your lips into a haven of sweetness reminiscent of your favorite Hostess treats.

Hindenburg

The Hindenburg disaster was an airship accident that occurred on May 6, 1937 in New Jersey. Filled with hydrogen, it caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. The accident caused 35 fatalities (13 passengers and 22 crewmen) among the 97 people on board (36 passengers and 61 crewmen), and an additional fatality on the ground.

Twinkies Scented Candle

“Indulge in the nostalgic aroma of Hostess’s delectable treat. This candle ensures a delightful and even burn that fills your space with the enticing fragrance of Hostess’s iconic flavors. Transform your surroundings into a haven of sweetness as the warm glow and triple wicks create a cozy atmosphere reminiscent of your favorite Hostess treats.”

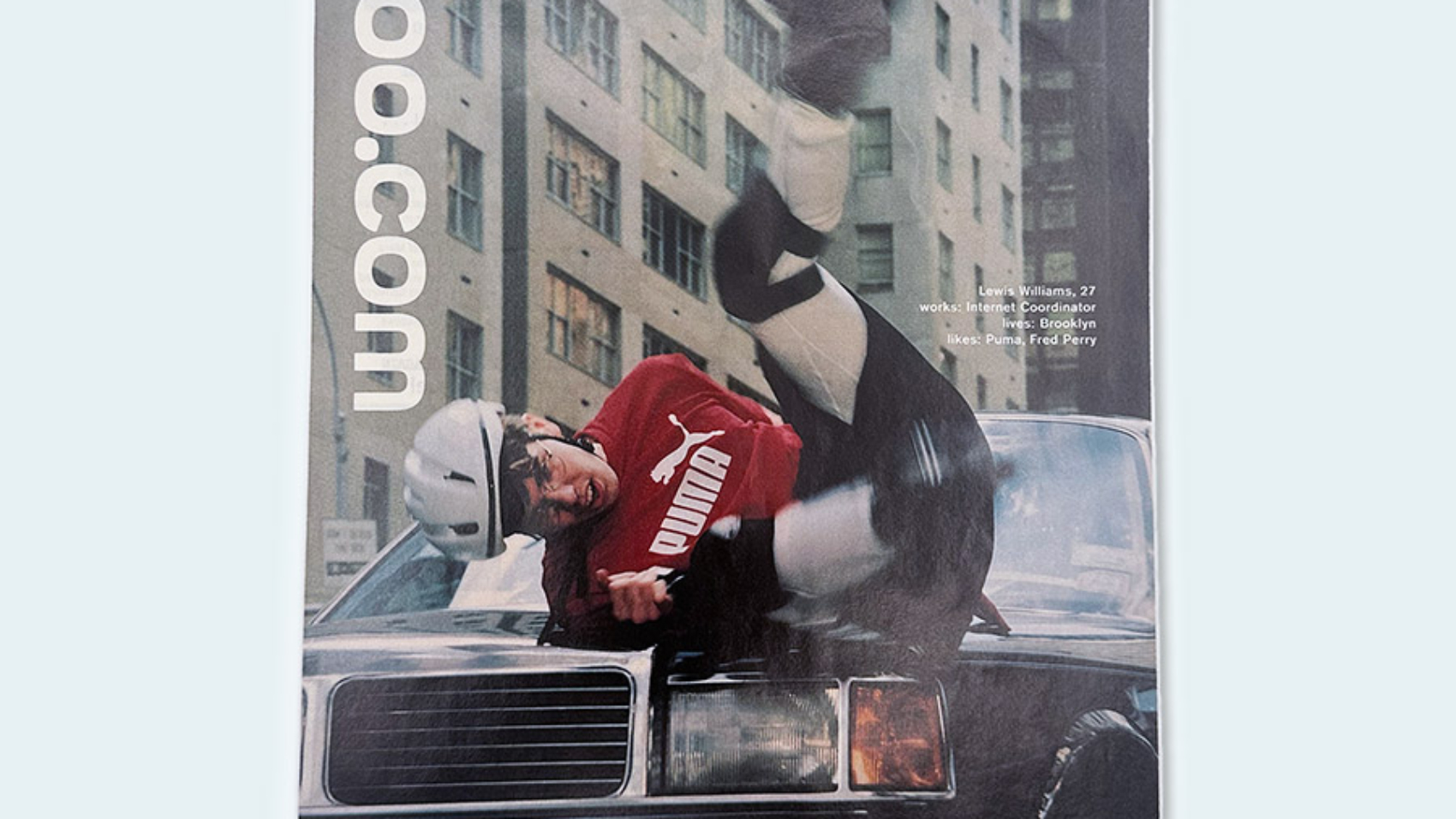

Boo.com

Founded in 1998, Boo.com wanted become the largest online sports e-retailer in the world, planning to set up stores in both Europe and America simultaneously. The company spent $135M in venture capital in just 18 months and went out of business in 2000.

The boo.com website was widely criticized as poorly designed for its target audience of young, wealthy and fashionable people between 18 and 24 years old. The site’s interface was complex and included a hierarchical system that required the user to answer four or five different questions before sometimes revealing that there were no products in stock in a particular sub-section.

Yugo

Discontinued in 2008, the Yugo was a small car made in the former nation of Yugoslavia that survives in the American consciousness as the ultimate automotive failure. Poorly engineered, ugly, and cheap, it survived much longer as a punch line for comedians than it did as a vehicle on the roads.

Lotus 1-2-3

Lotus 1-2-3 was the state-of-the-art spreadsheet and the standard throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, part of an unofficial set of three stand-alone office automation products that included dBase and WordPerfect, to build a complete business platform.

During the early 1990s, Windows grew in popularity, and along with it, Excel, which gradually displaced Lotus from its leading position as Lotus had suffered technical setbacks in this period. A planned total revamp of 1-2-3 for Windows fell apart, and all that the company could manage was a Windows adaptation of their existing spreadsheet with no changes except using a graphical interface. Additionally, several versions of 1-2-3 had different features and slightly different interfaces.

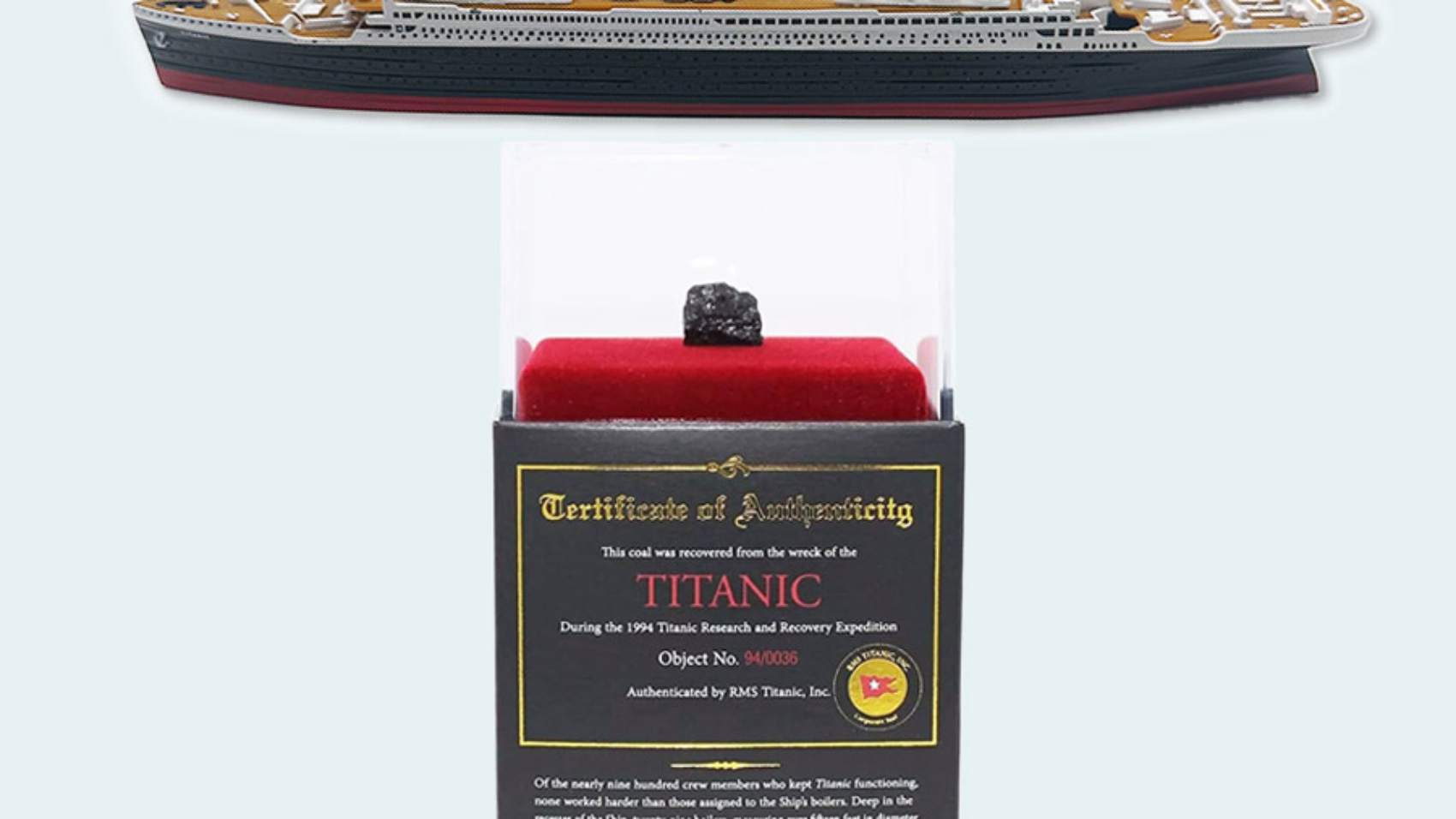

Titanic

The Titanic was a British ocean liner that sank on April 15, 1912 as a result of striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southhampton, England to New York City. 1496 of the 2224 passengers died making it the deadliest sinking of a single ship at the time. The Titanic received a series of warnings from other ships of drifting ice in the area, but the captain ignored them. It was generally believed that ice posed little danger to large vessels. The Titanic only had enough lifeboats to carry about half of those on board, while the lifeboats were only filled up to an average of 60%. The “women and children first” protocol was generally followed when loading the lifeboats, and most of the male passengers and crew were left aboard. Women and children survived at rates of about 75% and 50%, while only 20% of men survived.