In the 2023-2024 season, the Detroit Pistons set an NBA record 28 game losing streak.

Racine Legion

From 1922-1924, the Racine Legion was an NFL team in Racine, Wisconsin. Despite performing well, the team failed because of finances due to small home crowds. In it’s inaugural season the team finished in 6th place in a league of 18 teams.

Avaya Stadium (bankrupt sponsor)

In 2014, Avaya signed a $20 million, 10-year deal for naming rights for the home of the San Jose Earthquakes. Once it filed for bankruptcy in 2017 it was renamed PayPal Park.

In 2023, Avaya, the one-time networking and unified communications industry stalwart, filed for bankruptcy a second time and was delisted by the NYSE. At a time when both the collaboration and contact center markets were been red-hot, Avaya’s $3.4 billion massive debt obligations prevented it from executing in these areas.

National Car Rental Center

In 1998, the Florida Panthers new home was called the National Car Rental Center. It’s now called Amerant Bank Arena.

In 1996, National was acquired by Republic Industries (later renamed AutoNation). AutoNation spun off its car rental properties as ANC Rental in 2000. ANC filed for bankruptcy a year later; its properties were sold to Vanguard Automotive Group in 2003. On August 1, 2007 Enterprise Rent-A-Car assumed control of Vanguard Automotive Group.

PSINet Stadium

In 1999, PSINet signed a naming rights agreement for the home of the Baltimore Ravens until it filed for bankruptcy in 2002. It’s now called M&T Bank Stadium.

PSINet, a telecommunications company, struggled with its debt load, an unfocused business plan, and the pressures of over-expansion.

MCI Center

In 2006, Verizon purchased MCI and changed the name of the arena to Verizon Center after 9 years as MCI Center. Now it’s called Capital One Arena and is the home arena for the Washington Wizards, Washington Capitals, and Georgetown University’s men’s basketball team.

MCI filed for bankruptcy in 2002 after an accounting scandal in which several executives were convicted of a scheme to inflate the company’s assets.

CMGI Field

In 2000, CMGI signed a 15 year, $114 million deal for the naming rights for the New England Patriots’ stadium.

CMGI, whose vastly depreciated Internet holdings made it a poster child for the failed dot.com era, transitioned it’s naming rights to Gillette.

Enron Field

In 1999, Enron paid $100 million over 30 years to name the Houston Astros ballpark. After the Enron scandal of 2001, the Astros and the bankrupt Enron came to an agreement to end the deal and rename the stadium in February 2002, which is now called Minute Maid Park.

In 2007, Enron hid mountains of debt and toxic assets from regulators and investors using a combination of shell companies (special purpose entities), creative revenue recognition, aggressive mark to market practices, and outright fraud. None of this would have been possible without compromising the two parties in charge of their governance and oversight, their Board of Directors and their Audit Partner, Arthur Andersen. Enron didn’t have effective board oversight because the board relied on data from the executive team and never once sought independent validation or forensic analysis of the increasingly complex organization they oversaw. The company peaked at a $70B market cap and 30K employees. Top executives were paid $55M in bonuses and cashed in $116M in stock, while employees lost $1.2B in retirement funds.

Trans World Dome

Trans World Dome, which hosts concerts, major conventions, and sporting events in St Louis, ended the naming rights in 2001 when TWA was acquired by American Airlines, who already had its name on two NBA/NHL venues in Dallas and Miami. The arena, which lost the St. Louis Rams, is now called the Dome at America’s Center.

In 2001, TWA flew its final flight. The company was sold to American Airlines after decades of saddling debt. In 1991, the company was forced to sell its lucrative London routes — accelerating their demise.

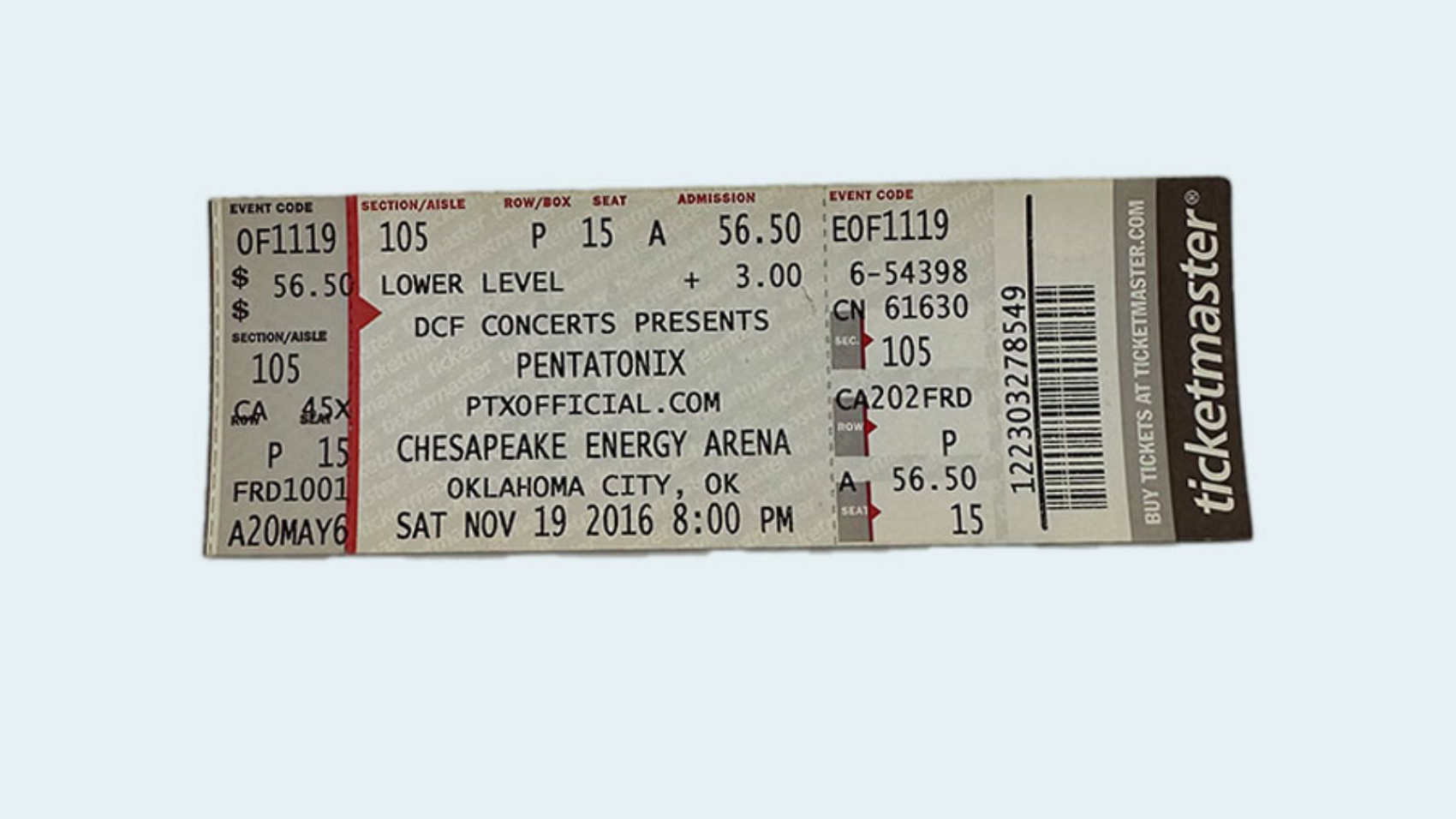

Chesapeake Energy Arena

In 2021, Chesapeake Energy terminated its 12 year arena naming rights agreement with the Oklahoma Thunder two years early leading to the new name of Paycom Center.

In 2020, the company filed for bankruptcy protection with $7 billion in debt.